The muon’s magnetism remains to be robust. Its most exact measurement but is according to a sequence of earlier outcomes — and seals an embarrassing discrepancy with many years of theoretical calculations that had predicted a barely weaker magnetism for the elementary particle.

However though the odd behaviour of the muon — a heavier cousin of the electron — was as soon as seen as a doable omen of recent physics, outcomes previously two years counsel that the speculation facet may not want main amendments in spite of everything.

The Muon g – 2 experiment on the Fermi Nationwide Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) outdoors Chicago, Illinois, has succeeded in doubling the precision of its earlier measurement of the muon’s magnetic second, which it had reported two years in the past. “We seem to substantiate that earlier measurement — and, principally, that we had been proper,” says Muon g – 2 physicist Svende Braun on the College of Washington in Seattle. The group introduced its newest replace in a webcast on 10 August and has submitted a paper1 to Bodily Overview Letters.

The improved precision is “an awesome achievement”, says Zoltan Fodor, a theoretical physicist at Pennsylvania State College in College Park, who noticed a preprint describing the Muon g – 2 outcomes.

The anomaly

Muons are just like electrons, however 207 occasions extra huge. They’re additionally unstable: they’re created in particle collisions and decay into their lighter cousins shortly afterwards.

The magnetism of the muon originates primarily from the truth that the particle has an electrical cost and that it spins on itself. These two elements mix to make the particle act like a tiny bar magnet, with a area energy prescribed by quantum physics to be equal to 2, within the applicable models. This magnetic area is enhanced by ‘digital particles’ that come out of empty house solely to vanish a fraction of a second later. Physicists denote the ensuing deviation from the ‘vanilla’ worth of two as g – 2.

In precept, the usual mannequin of particle physics predicts how every sort of particle within the Universe contributes to g – 2 by way of its digital avatars. However there is no such thing as a recognized means of calculating this precisely, and even approximate calculations are extraordinarily complicated. For many years, physicists have supplemented the speculation with real-world knowledge about digital particles coming from collider experiments to acquire a predicted worth for g – 2.

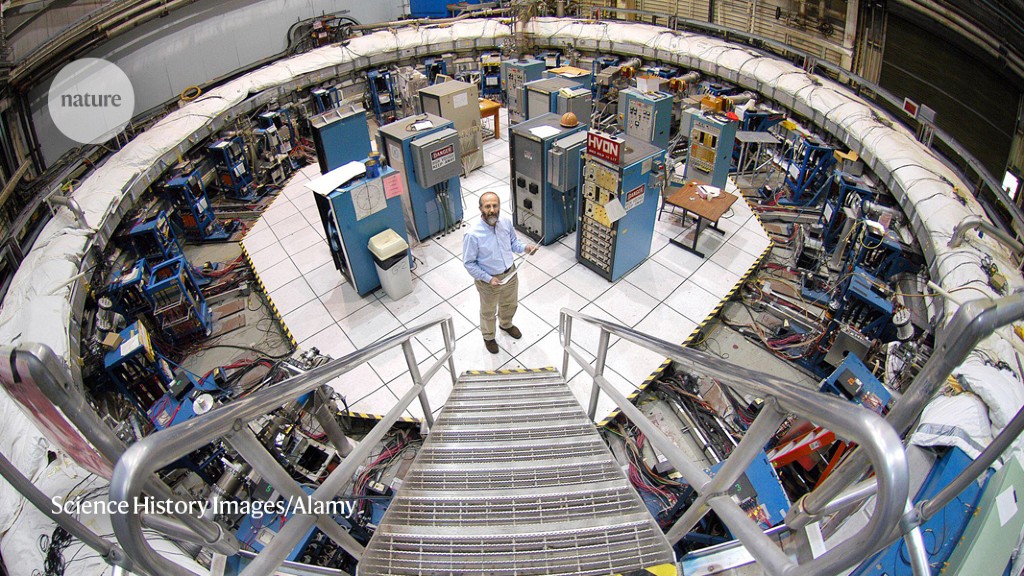

In 2001, an experiment at Brookhaven Nationwide Laboratory in Upton, New York, made probably the most exact measurement but of the muon’s magnetism2, and located it to deviate from the theoretical predictions that had been then state-of-the-art. To analyze this discrepancy, physicists rebuilt the Brookhaven experiment at Fermilab, which concerned transporting a 15-metre-wide round magnet to Illinois utilizing barges and particular vans.

The rebooted Muon g – 2 experiment began taking knowledge in 2018. The outcomes it reported in 20212 had been an evaluation of that first batch of knowledge, and confirmed the Brookhaven findings. At present’s outcome incorporates knowledge from two extra runs, from 2019 and 2020. The authors estimate the error bar of their worth of g – 2 to be now simply 201 elements per billion.

Judging from the usual, data-driven predictions alone, the most recent measurement of g – 2 would appear to deviate from idea (as up to date most lately in 20203) by round two elements in 1,000,000. And the shrunken uncertainty would for the primary time clear the ‘5 sigma’ bar that particle physicists often require to say a discovery.

However beginning with outcomes by Fodor and his colleagues in 20214, another approach for calculating g – 2 has emerged, which doesn’t require collider knowledge and as an alternative makes use of laptop simulations. When the Muon g – 2 measurement is in contrast towards this new prediction, the discrepancy primarily disappears. A number of different groups have adopted up with their very own laptop simulations, which have tentatively converged with these by Fodor’s group. Fermilab scientist Ruth Van De Water, a number one member of certainly one of these teams, says she expects any lingering disagreements to be sorted out “within the subsequent yr or two”.

Contemporary spin

A separate experimental outcome, posted earlier this yr on arXiv5, launched an sudden twist to the story. Knowledge from collisions of electrons and their antiparticles, positrons, from an accelerator experiment referred to as CMD-3 in Novosibirsk, Russia, appear to disagree with these from different electron–positron colliders. When fed into the theoretical calculations for g – 2, they, too, make the discrepancy disappear.

Earlier electron–positron experiments had been additionally not all completely in line with each other, Van De Water factors out. “At this level, I might take the data-driven estimates with some warning till issues are sorted,” she says.

“Sadly, we don’t know at this second the place this distinction comes from, and that is the primary subject which we should always perceive,” says CMD-3 physicist Fedor Ignatov on the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics in Novosibirsk, Russia. One risk is that a number of the earlier experiments didn’t absolutely take note of the peculiarities of their detectors.

Because the three data-taking runs that had been included within the newest Muon g – 2 evaluation, the experiment has had three extra runs; its sixth and remaining one was accomplished on 9 July, says Peter Winter, a physicist at Argonne Nationwide Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois, who’s the co-spokesperson for the experiment. The collaboration expects its measurement to cut back the uncertainty additional right down to 0.14 elements in 1,000,000 by the point publishes its remaining outcomes a couple of years from now.